When Kerry Stormed D.C.

Mini Teaser: John Kerry was just five years out of Yale when he testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and became an instant celebrity.

DURING THE Vietnam War, there were many memorable hearings at the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, but none resonated with the raw power and eloquence of John Kerry’s on April 22, 1971. It was a time of crisis in America—a war seemingly without end for a goal still without clarity, in a country split not only on the war but also on a host of emotional political, cultural and social issues.

DURING THE Vietnam War, there were many memorable hearings at the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, but none resonated with the raw power and eloquence of John Kerry’s on April 22, 1971. It was a time of crisis in America—a war seemingly without end for a goal still without clarity, in a country split not only on the war but also on a host of emotional political, cultural and social issues.

When Kerry entered room 4221 of what is now called the Dirksen Senate Office Building, its impressive walls covered with maps and books and with nineteen senators seated behind a huge U-shaped table, he did more than add instant credibility to the dovish cry for Congress finally to do something about ending the war, even going so far as to advocate cutting off funding; he personalized the war that for so many others still seemed a puzzling, costly embarrassment in an unfamiliar corner of the world.

Kerry was a 1966 Yale graduate who had volunteered for duty in Vietnam, where he served honorably, winning two medals for courage and three Purple Hearts. “I believed very strongly in the code of service to one’s country,” he said. By that time, 56,193 Americans had died in and around Vietnam, and campuses were ablaze with antiwar rallies. Many students escaped military service by joining the National Guard or fleeing to Canada.

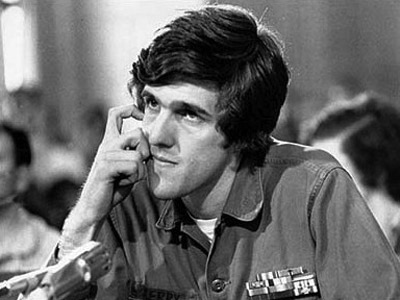

Dressed in green army fatigues, with four rows of ribbons over his left pocket, the twenty-seven-year-old survivor of dangerous Swift Boat missions leveled a blistering attack on American policy in Vietnam, his New England accent adding a dimension of authenticity to the sharpness of his critique. When he finished his testimony an hour later, he had become, in the words of one supporter, an “instant celebrity . . . with major national recognition.”

Speaking on behalf of more than a hundred veterans jammed into the Senate chamber and more than a thousand others camped outside to demonstrate against the war, Kerry demanded an “immediate withdrawal from South Vietnam.” He came to Congress, and not the president, he said, because “this body can be responsive to the will of the people, and . . . the will of the people says that we should be out of Vietnam now.”

If Kerry had simply expressed this demand, and not amplified it with reports of American atrocities, he likely would have avoided the devastating criticism that hounded him throughout his political career—criticism that eventually morphed into charges of treason and treachery, deception and lies, cowardice and even more lies, undercutting his presidential drive in 2004.

Kerry told the committee that in Detroit a few months earlier, 150 “honorably discharged . . . veterans” launched what they called the “Winter Soldier Investigation.” In 1776, Kerry said, the pamphleteer Thomas Paine had written about the “sunshine patriot,” who deserted his country when the going was rough. Now, Kerry continued, the going was rough again, and the veterans who opposed the war felt that they had to speak out against the “crimes which we are committing.”

Kerry emphasized the word “crimes,” and most of the senators and all of the journalists leaned forward in their seats. A hush fell over the room. I was among the reporters covering Kerry’s testimony. During the 1960s and early 1970s, when, as diplomatic correspondent for CBS News, I reported on a number of important foreign-policy deliberations at the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, I generally stood with my camera crew in the back of the room. Rarely was it crowded. Most of the radio, newspaper and magazine reporters gathered around a large rectangular table near the tall windows. A second large table was on the other side of the room. Between the two and directly behind the witness table were rows of chairs for aides, guests and tourists.

On this very special day, however, the seating rules were suspended. I arrived early, but even so most of the seats were already taken. The veterans squeezed into the back of the room, most standing, very few seated. I spotted one empty chair in the front row and ran for it, beating out a network competitor by half a step. I was lucky; I had a great seat, no more than six feet from where this young antiwar leader was to deliver testimony that yielded the immediate advantage of dominating the news that day. Kerry hoped this would be the case, but it also carried the unintended consequence of providing ammunition to his political opponents to prove he was unworthy of higher office.

KERRY STARTED with his most explosive charge. He quoted the “very highly decorated veterans” who had unburdened themselves in Detroit, saying:

They told the stories at times that they had personally raped, cut off ears, cut off heads, taped wires from portable telephones to human genitals and turned up the power, cut off limbs, blown up bodies, randomly shot at civilians, razed villages in fashion reminiscent of Genghis Khan, shot cattle and dogs for fun, poisoned food stocks, and generally ravaged the countryside of South Vietnam.

Kerry continued, “The country doesn’t know it yet, but it has created a monster, a monster in the form of millions of men who have been taught to deal and to trade in violence.” He was describing his buddies, the Vietnam veterans on the Washington Mall, and many others, the “quadriplegics and amputees” who lay “forgotten in Veterans’ Administration hospitals.” They weren’t “really wanted” in a country of widespread “indifference,” where there were no jobs, where the veterans constituted “the largest corps of unemployed in this country,” and where 57 percent of hospitalized veterans considered suicide.

I suspect most of us in room 4221 were shocked by Kerry’s description of the veterans just back from the Vietnam War. I had always thought of the American soldier as a brave, patriotic and honorable warrior—that had been my personal experience in the U.S. Army—not as a “monster . . . taught to deal and to trade in violence” who “personally raped, cut off ears, cut off heads,” comparable to the rampaging legions of Genghis Khan in the thirteenth century. Kerry’s words evoked images totally foreign to the American experience, certainly to me. I wondered: Could Kerry be right? After all, he had fought in Vietnam. I hadn’t.

We were by then familiar with the so-called credibility gap, the “five o’clock follies” in Saigon, and White House briefings pumped up with artificial optimism and more than an occasional fib. And if Kerry was right, how could the senators have been so wrong, so gullible? How could we Washington journalists, who had covered so many other hearings, speeches and backgrounders, have been so misled? More pointedly, how could we have allowed ourselves to be so misled? Could Kerry’s portrait of the American veteran actually be a portrait of Dorian Gray in khaki?

Listening to this decorated veteran, a Yale graduate with an old-fashioned sense of service and patriotism, I thought of the political scientist Richard Neustadt’s emphasis on the importance of “speaking truth to power.” I had the feeling that this veteran was speaking truth to Congress and to the American people, though with a flair for hyperbole that he was later to regret. Often, during his testimony, I found myself in a state of semi-hypnosis, pen in hand but not taking notes, absorbed by the boldness—and relevance—of his criticism. The massacre at My Lai was in the air. Army lieutenant William L. Calley had been on the cover of Time. If a lieutenant could burn down a village with a Zippo lighter, was it not possible that another lieutenant could be high on drugs—and then rape and kill? Could Kerry be right? I had once been a hawk on the Vietnam War—I had thought that stopping Communism in Southeast Asia was as sound a strategy as stopping it in Europe. But after the Tet Offensive in early 1968, and after General William Westmoreland’s stunning request for an additional 206,000 troops, to be added to the 543,000 troops already in theater (a request fortunately rejected by the new secretary of defense Clark Clifford), I began to change my mind not only about the strategy but also about the very purpose of the war. That day, Kerry pushed me (and many other Americans) over the brink. I began to think that the United States had made a terrible mistake in Southeast Asia and that it was time to admit it and take the appropriate action.

Indeed, every now and then, a question crystallizes a national dilemma. Kerry asked: “How do you ask a man to be the last man to die in Vietnam? How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?” If the war was a mistake, then why pursue it? One reason was that President Richard Nixon did not want to be, as he put it, “the first President to lose a war,” even though he knew that Vietnam was an “unwinnable proposition.” And then Kerry asked another question of equal pertinence: “Where are the leaders of our country?” Much to my surprise, as he listed his candidates for ignominy, he did not include Nixon or Henry Kissinger. “We are here to ask where are McNamara, Rostow, Bundy, Gilpatric,” he continued:

Image: Pullquote: From 1972, when he ran unsuccessfully for Congress, until 2004, when he ran unsuccessfully for president of the United States, Kerry’s world was intimately entangled with Vietnam.Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: From 1972, when he ran unsuccessfully for Congress, until 2004, when he ran unsuccessfully for president of the United States, Kerry’s world was intimately entangled with Vietnam.Essay Types: Essay