When Kerry Stormed D.C.

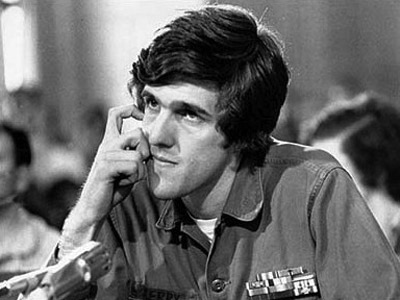

Mini Teaser: John Kerry was just five years out of Yale when he testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and became an instant celebrity.

WHEN KERRY returned to Boston a few days later, after the Washington demonstrations, he was in high spirits. His testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and his frequent appearances on television news and interview programs had propelled him into the national limelight and rekindled his political ambitions, which were never far from the surface in any event. He embarked on a nonstop speaking tour from one end of the country to the other, sparked by frequent TV debates with John O’Neill. One, on the Dick Cavett Show, attracted particular attention. O’Neill was strident, Kerry scholarly, clearly more adept at using television to fashion an image and project a message. “We knew that when he left the set,” Cavett recalled the occasion years later, “it wasn’t the last we were going to hear from him.” Kerry kept popping up on one program after another, selling himself as much as his antiwar theme. In a typical week, which happened to be the first week of October, Kerry spoke in Washington, DC, Kansas, Colorado, Nevada, California, Illinois and Massachusetts.

Throughout his whirlwind speaking tour, though, Kerry had one lingering problem, to which he returned time and again. He worried that the VVAW leadership was swinging too far leftward. If it continued to talk and act radical, it would lose the American people. Once during Dewey Canyon III he spotted a placard calling for “revolution.” Often he found himself arguing with other demonstration leaders about tactics. A few advocated violence; one even wanted to assassinate prowar senators rather than simply throw medals over a fence. Kerry, according to Randy Barnes, another key player, “constantly gave an impassioned plea to be nonviolent, work within the system.”

This problem came to a head at two VVAW meetings—in St. Louis in June and in Kansas City in November. Kerry attended the St. Louis meeting, and he may have attended the Kansas City meeting, too. (Some veterans remember him being there, while others swear he wasn’t.) What is indisputable is that Kerry left the St. Louis meeting, which was marked by hot arguments about the future direction of the VVAW, convinced that he had failed to persuade the leadership of this antiwar movement of veterans to stay “nonviolent” and to “work within the system.” A number of radical veterans wanted to initiate what the FBI later termed a “vastly more militant posture.” Kerry believed that there was a clear line separating antiwar sentiment from anti-American actions—these veterans, he thought, were moving dangerously close to that line. Kerry decided to resign from the executive committee of the VVAW, citing “personality conflicts and differences in political philosophy.”

From 1972, when he ran unsuccessfully for Congress, until 2004, when he ran unsuccessfully for president of the United States, Kerry’s world was intimately entangled with Vietnam. The seat for the Fifth Congressional District of Massachusetts opened when Republican F. Bradford Morse accepted the post of under-secretary-general of the United Nations. Morse promoted Paul Cronin, his legislative assistant, as the Republican candidate, and Kerry, sensing a superb opportunity to capitalize on his antiwar popularity, leaped into the fight as the Democratic candidate. Independent Roger Durkin, an investment banker, also entered the race. He ran ads sharply critical of Kerry’s liberal, antiwar positions, saying it was “important to defeat the dangerous radicalism that John Kerry represents.” He went further, actually questioning Kerry’s patriotism. Cronin watched from the sidelines, but the Sun, an archly conservative newspaper in Lowell, got behind Durkin’s attacks. An editorial blasted The New Soldier, a book Kerry had written about Dewey Canyon III. The book’s cover showed six veterans, bearded, with mustachios and headbands, looking like Castro warriors, holding up an American flag. The editorial, noting that the flag was being “carried upside down in a gesture of contempt,” angrily stated: “These people sit on the flag, they burn the flag . . . they all but wipe their noses with it.” Kerry tried to explain that an upside-down flag was a distress signal in international communications, not a sign of disrespect or contempt, but his explanation fell on deaf ears. Variations on this editorial ran in the Sun almost every day. Kerry fumed: “They were trying to paint a picture of me as some wild-assed, irresponsible, un-American youth. It was infuriating.” Kerry was to read similar editorials many more times over the years.

Then came the surprise that turned the election from a likely Kerry victory to a disheartening defeat. At the last minute, Durkin withdrew, throwing his support to Cronin, who gratefully accepted it. Kerry had been leading in the polls, but Durkin’s last-minute switch upset all political calculations. Cronin won; Kerry lost. The Boston Globe reported the next morning that Nixon, when told that Kerry had been beaten, slept like a baby.

IN 2004, it was not Durkin the man who resurfaced to defeat Kerry—it was his message, transmitted through the media by a well-financed veterans group called “The Swift Boat Veterans for Truth,” that undercut Kerry and destroyed his presidential prospects. The group was led by none other than John O’Neill. His hard-edged message, never wavering, echoed through time: Kerry was unpatriotic, he betrayed the nation and the veterans, he collaborated with the enemy and he was a traitor. And why? Because he used the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in April 1971 as a platform for criticizing American policy in Vietnam and, worse, for trashing the American warrior there as a brutal rapist who cut off ears and heads, shot at civilians, razed villages, and shot cattle and dogs for fun—all “in fashion reminiscent of Genghis Khan.” O’Neill and company had not forgotten Kerry’s testimony in room 4221.

From Nixon to Bush, conservatives used this line of attack against Kerry’s sharp critique of the Vietnam War, often questioning his patriotism and loyalty. Initially, Kerry and his friends considered it a sick joke. David Thorne recalled: “We both laughed at the fact that the President of the United States was after John.” Government agents shadowed Kerry at rallies and speeches. “It was just unbelievable,” Thorne told me. “He was as patriotic a guy as Yale University and the U.S. Navy ever produced. . . . I had come from a Republican family. Patriotism was in my veins. So we just thought because the war should end didn’t mean we deserved to have our basic rights infringed upon.” After a while, the joke was not funny. Kerry had raised a profound question—“How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?” If the Vietnam War was a mistake, as Kerry believed, then there was no point in wasting additional lives. Let the “last man” really be the last man to die for a mistake. Nixon as president could not answer the question without either denying that the war was a mistake or admitting that it was. Denying meant, in effect, a continuation of the war; admitting meant an end to the war. He chose to do neither. Like an old political fighter, Nixon was content to engage, defeat and destroy Kerry, and he pulled no punches in this determined effort. Dissent was translated as opposition not only to his policy but to the nation and its destiny. Nixon was convinced he was right.

Kerry approached the argument from a different perspective. He believed his dissent on Vietnam was borne of his bloody experience there—it was not an academic exercise. He also believed that his dissent was in a noble American tradition. As Paul Revere and John Adams had objected to the king’s rule, so Kerry was objecting to the president’s policy. It was a moral obligation of the patriot to help his country face and correct a terrible mistake. His criticism was not intended to offend his countrymen but rather to help them emerge from the darkness of this blunder in Southeast Asia into the bright light of a better policy, consistent with the noble principles of American freedom.

What we saw emerging in the troubled year of 1971 was a new set of battle lines around two old issues—a definition of patriotism that fit the times and the changing value of military service as an asset for presidential leadership. On patriotism, dueling definitions were angrily debated without resolution but with a deepening bitterness that reflected the divide in the nation’s politics. On the value of military service, the pain of Vietnam shattered the old, comfortable conviction that service in uniform, under fire in the nation’s defense, strongly enhanced a candidate’s image of presidential authority and leadership.

Marvin Kalb is a guest scholar at the Brookings Institution and Edward R. Murrow Professor Emeritus at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. Over his thirty-year broadcast career, he served as CBS’s and NBC’s chief diplomatic correspondent, Moscow bureau chief and moderator of Meet the Press. His most recent book is The Road to War: Presidential Commitments, Honored and Betrayed, from which this article is adapted.

Image: Pullquote: From 1972, when he ran unsuccessfully for Congress, until 2004, when he ran unsuccessfully for president of the United States, Kerry’s world was intimately entangled with Vietnam.Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: From 1972, when he ran unsuccessfully for Congress, until 2004, when he ran unsuccessfully for president of the United States, Kerry’s world was intimately entangled with Vietnam.Essay Types: Essay