When Kerry Stormed D.C.

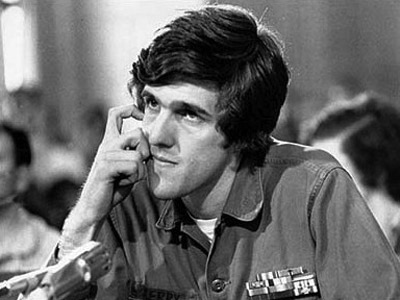

Mini Teaser: John Kerry was just five years out of Yale when he testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and became an instant celebrity.

Haldeman: “He is, he did a hell of a job.”

Nixon: “He said he was very effective.”

Haldeman: “I think he did a superb job at the Foreign Relations Committee yesterday. . . . A Kennedy type—he looks like a, looks like a Kennedy and talks exactly like a Kennedy.”

Kerry had hit the White House with the force of an unwelcome guest. He demanded an end to the war. Impossible, for Nixon. He demanded access to an administration official. Denied. He demanded a total change in policy. No way. “Disgraceful!” Kerry later told reporters. “We had men here with no legs, men with no arms, men who got nine Purple Hearts, and they ignored that simply because of the politics.” Ironically, Kerry had impressed Nixon so much that the president decided to take even stronger action against the demonstrating veterans.

David Thorne, once Kerry’s brother-in-law and now a close friend and adviser, told me that “the White House was sending out guys to start fights and to try anything they could do to discredit vets on the Mall. . . . We heard that Nixon was nuts about this. He was doing things in the dirty tricks department.” Brinkley said that the administration created a “get John Kerry campaign.” The exact words of a memo from White House special counsel Chuck Colson were: “I think we have Kerry on the run . . . but let’s not let up, let’s destroy this young demagogue before he becomes another Ralph Nader.’” Columnist Joe Klein, who covered Kerry at the time, reported: “They were investigating John Kerry up and down and Colson said to me, ‘We couldn’t find anything. There wasn’t anything we could find.’” Colson concocted the crazy idea of finding another John Kerry to destroy the real John Kerry. “We found this guy John O’Neill to run a group that would counter the Vietnam Veterans Against the War.” O’Neill was also a Swift Boat veteran, but he believed in the war and hated Kerry. They called the new group “The Vietnam Veterans for a Just Peace.” Just as O’Neill was central to derailing Kerry’s 2004 run for the presidency, so too was he central to Nixon’s effort to undermine Kerry in 1971. O’Neill met with administration leaders, including the president. “Give it to him,” Nixon urged. “Give it to him. And you can do it because you have a—a pleasant manner. And I think it’s a great service to the country.” Colson helped O’Neill organize media interviews around the country.

More White House audiotape shows Colson trying to buck up Nixon’s sagging spirit:

Colson: “And this boy O’Neill, who is, God, you’d just be proud of him. These young fellows, we’ve had some luck getting them placed.”

Nixon: “Have you?”

Colson: “Yes, sir.”

Nixon: “Good.”

Colson: “And they’ll be on. We’ll start seeing more of them. They would give you the greatest lift.”

The White House was obviously concerned that Kerry was becoming too much of a television star, spreading his antiwar message from one program to another. The White House was also concerned that the VVAW was generating too much sympathy and support. The war was still in progress, yet here were veterans demonstrating against it. They had come from all over the country, many in khaki, bearded, wearing headbands and sporting antiwar slogans on their T-shirts. Several were on crutches, a few in wheelchairs. On occasion, because there was no violence, they looked like respectable hippies promoting an antiwar message, some armed with nothing more lethal than a guitar. They marched through Washington, past the Lincoln Memorial, past the State Department, past the White House. Once, according to CBS correspondent Bruce Morton, who covered the week-long demonstration, “They passed some smiling members of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and a woman said: ‘This will be bad for the troops’ morale,’ and someone answered, ‘These are the troops.’” A national poll at the time revealed that one in three Americans approved of the VVAW’s demonstration, hardly an overwhelming number, but still encouraging to the VVAW’s leadership, including Kerry, who knew they had started from nowhere and now found themselves at 32 percent. Not bad for one week’s work. Forty-two percent disapproved. With the nation at war, the White House had expected a higher level of disapproval.

ON FRIDAY, April 23, the last day of the Washington demonstration, a hundred or so veterans threw their medals over a hastily built fence near the Capitol in a show of anger and disgust. Kerry threw ribbons, not medals. One veteran, making no distinction, said: “I got a Silver Star, a Purple Heart . . . eight air medals, and the rest of this garbage. It doesn’t mean a thing.”

If it didn’t “mean a thing” to this veteran, it did to many White House supporters, who, fearing their popular support dwindling, quickly denounced this display of anger as disrespectful to both the country and to the troops still fighting in Vietnam. Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott, a Pennsylvania Republican, dismissively described these veterans as only “a minority of one-tenth of one percent of our veterans. I’m probably doing more to get us out of the war than these marchers.” Commander Herbert B. Rainwater of the Veterans of Foreign Wars chimed in with a double put-down: the antiwar veterans were too small a group to generate so much news, and besides they were not representative of the average veteran. Conservative columnist William F. Buckley Jr. trashed Kerry as “an ignorant young man,” who had crystallized “an assault upon America which has been fostered over the years by an intellectual class given over to self-doubt and self-hatred, driven by a cultural disgust with the uses to which so many people put their freedom.”

Nixon appreciated these measured expressions of support. With the war on the front burner of popular concern, sparking one Washington demonstration after another (one day after the VVAW’s protests, known as Dewey Canyon III, ended, a huge peace march arrived in the nation’s capital), Nixon yearned for good news, for the joys of a long weekend at Key Biscayne, but could find little in those days that could be defined as good. And Dewey Canyon III reminded him of a recurring nightmare that, though he tried, he could not escape. He worried that some Vietnam veterans might be returning not as the “monster” Kerry described, but as drug addicts. In his splendid biography of Nixon, journalist Richard Reeves wrote that the president’s worry was political. Reeves explained:

What worried him most was the effect on Middle American support for the war if clean-cut young men were coming back to their mothers and their hometowns as junkies. Suddenly drug use was a national security crisis. “This is our problem,” wrote Nixon on a news summary report of a Washington Post story that quoted the mayor of Galesburg, Illinois, saying that almost everyone in that conservative town wanted their sons out of Vietnam.

NBC News reported that half of a contingent of 120 soldiers returning to Boston had drug problems. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that each day 250 soldiers were returning with duffel bags full of drugs—as Reeves put it, “for their own use or to sell when they got back home.”

“As Common as Chewing Gum” was the way Time headlined a story about drug use by the troops. A GOP congressman, Robert W. Steele of Connecticut, told the White House that, based on his recent visit to Vietnam, he estimated that as many as forty thousand troops were already addicts. In some units, he said, one in four soldiers was a drug user. By May 16, the problem worsened, and the New York Times headlined its story “G.I. Heroin Addiction Epidemic in Vietnam.”

On the Washington Mall, however, it was not drugs that disturbed Nixon; it was the immediate problem of the antiwar message that Kerry and the veterans were pushing. Day after day, they dominated the evening newscasts and the morning headlines, and Congress—ever sensitive to media swings—felt emboldened to press forward with legislation to end America’s involvement in Vietnam. It would take another two years for Congress to achieve that goal, and another four years for the United States finally to leave Vietnam, its tail between its legs. But Kerry felt that the continuing VVAW effort was paying big dividends. During the Detroit conference, which he attended, and during Dewey Canyon III, which he helped lead, Kerry felt that the whole country was moving toward a historic decision to end the war. Since that was his goal, he was pleased. But he was soon to learn, as was the entire nation, that ending a war in defeat, or what was widely perceived to be a defeat, would prove to have a profoundly disruptive effect on a proud people who had never before experienced the trauma of losing a war. The French had lost wars, as had the Russians, Germans and Japanese, but never the Americans, not until they bumped into Vietnam.

Image: Pullquote: From 1972, when he ran unsuccessfully for Congress, until 2004, when he ran unsuccessfully for president of the United States, Kerry’s world was intimately entangled with Vietnam.Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: From 1972, when he ran unsuccessfully for Congress, until 2004, when he ran unsuccessfully for president of the United States, Kerry’s world was intimately entangled with Vietnam.Essay Types: Essay